Music as a Form of Serial Fiction

April 18, 2023

The telling of a fictional tale through music is something that can be seen as long as songs have had lyrics. Stories told lyrically, while somewhat at the wayside to personal experience in songs, is a very way of sharing a narrative, though often not seen quite so highly as other mediums due to its limitations of length. Despite this, this medium has far more to tell then what meets the eye, especially when the idea of the music albums comes into play.

The concept album, originally created in folk circles in the 1940s, has no one clear definition. While the concept is far more subjective, the simplest answer is an album focused on a theme, idea, or in this case, an overarching story. This use of music, rather than using the run time of one single song to tell a story, follows a format more akin to serial fiction, using each song like another book in a series. It is my opinion that this use of music, while far less common, is superior in telling stories due to this additional length, and ability to change. To be clear, I am not talking about musicals when I talk about this, as those are reliant on non-musical narratives and visuals, and are styled drastically different than any other type of music.

There’s many positives music has to bring to the table of narrative, particularly in the use of motif and tone. These all allow for songs to individually tell stories with both words and instrumentals to go with them. With all the ways it can be used, examining one example would leave a lot out, so I will be looking into two notable examples, all with varying popularity, use of this medium, and country of origin.

I think the best place to start is with the newest of the three, Takuya Yamanaka’s MILGRAM, named after the 1961 Yale psychology experiment. The ongoing 2020 Japanese web series is a poster child for the use of motifs (both in its music and animated music videos), showing how far music can create ideas as effective as more visual mediums, while adding subjectivity that those do with less ease. We follow Es, the prison guard and the prison warden jackalope as we are shown the stories of 10 people, all responsible for a death, circumstances drastically varying. The series’s main point of interest would usually be the audience interaction and effect on the story, using voting to decide the innocence of the character’s ideas with each music video. Despite this, I would rather shift the focus to the music and videos in question, using music video 5 and 8 of trial 1 as reference for these. Video 5, titled “スローダウン” (eng: Throwdown), follows Shidou Kirisaki, and, through a very subjective set of metaphorical scenes, what is often interpreted as his attempts to save his wife. Representing his role as a doctor with a gardener, the song tells us of Shidou telling various families of patients he could have saved, yet didn’t, paired with the video which shows him taking flowers from plants for a collection, killing them in the process. This achieves a sinister tone it needs through the use of colors and motif that reminds me slightly of the one seen in the live action Hannibal show, that is to say, a strange, fancy, and almost serial killer esc environment and colors. Though it could be confused for mundane, this motif allows a clear concept of wrongdoing we are only given a slight concept of, yet just enough to let our ideas fill in the rest. On the opposite side of the spectrum is Video 8, known as おまじない (eng: Magic and/or Good Luck Charm), is our introduction to Amane Momose, the youngest of our main characters at only 12. The video is by far the most upbeat and colorful of the first 10, featuring a cast of animals and mascot adjacent teachers throughout to represent characters from her past. Due to this representing her concept of the situation, Amane’s lyrics and beat stay happy and, yet imply religious connotation, referring to the listener as “神様” (eng: a respectful way to refer to a god) and using almost out of place church bells and choir for the bridge, with promises she has gotten better after apologizing for a mistake. When paired with the visuals of her helping a friend with medical attention and being punished for it, this song is able to give us a very clear idea of a cult, without really breaking the cheery upbeat concept of facade.

The concept of motif is quite important for the use of story in music, but is difficult to really make work without connecting themes to keep the story together.

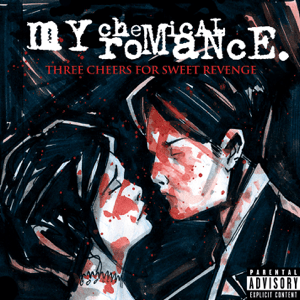

One example of an amazing use of themes in music based storytelling can be seen in the American album Three Cheers for Sweet Revenge. My Chemical Romance’s 2nd studio album, released 2004, is one of many by them to include a self contained story over a majority of songs. Continuing the contained story of the final song of their initial album, titled Demolition Lovers, (detailing the committed marriage and death of our main characters,) Three Cheers follows the unnamed husband’s resurrection, as well as his goal to kill 1,000 evil souls with the promise of being reunited with his wife. While the story seems to be simply about death, much like how many preserve the band’s music, the main overarching theme of this album, even in songs unrelated to the story, is reaction to death and mental health, as we see our main character fall apart due to the grief and actions he must commit. This theme of mental health, even when used in the songs separate from the story, uses the variety of such a complicated concept to really bring our main character’s struggle into focus, making his final lines of “I tried! I tried!” all the more harrowing. Personally, I think this use of story mixing with theme through music is best shown in the second track, Give ‘Em Hell, Kid, in which our protagonist starts his attempt to save his wife. While this song is far from the lowest we see this character’s mental stability, the use of repetition and highlighting of his situation only really possible in a musical medium, the upbeat song is able to give us an idea of a reluctantly upbeat start, while still showing his struggles with being alone. This album’s story is a clear cut example of the interpretive nature of music working in its favor, as this story would struggle with the 40 minute length, even with visuals due to its less set in stone ideas and characters. This shows us the ability to use the indisputable strength of audience interpretation as a tool used to its extreme, a very powerful tool if used right.

All in all, these two examples tell us a lot about music as a medium for serial fiction. When it comes down to it, music and television have the same ability in this sense, just with differing strengths. There are plenty of examples of the beauty of this medium and its storytelling, and it deserves as much consideration as TV or podcast when telling stories.